Widely used lab culture tests for Legionella bacteria have shortcomings that could leave building users at risk, Greg Rankin, CEO of testing company Hydrosense, told Facilities Dive. The bacteria is in the news after six people died, and dozens were sickened, in New York City last month from Legionnaire’s disease attributed to the bacteria, which was found in commercial water towers.

Lab culture tests typically take between 10 days and two weeks before results are available, a time gap that can leave people exposed to high concentrations of the bacteria, Rankin said.

“If you’re testing a [drinking] fountain in the lobby of a busy hotel, and it comes back positive, the number of people who come across that in two weeks can be phenomenal, so the risk is absolutely profound,” said Rankin.

Even if the result is negative, the water system can still pose a risk because the test is a snapshot of what was happening two weeks ago, not what’s happening today, he said.

“A negative result is kind of meaningless because Legionella can double in 24 hours, so all it tells you is the system was safe 10 days ago or two weeks ago,” he said.

A growing problem

The number and severity of Legionella outbreaks have been increasing in the United States at a 9.3% annual rate since 2002, with the growth attributed in part to climate change, a 2023 study in the Journal Epidemiology and Infection found. An aging population and water infrastructure problems are other potential contributors.

New York City is one of the few U.S. jurisdictions to require building operators to test their water cooling towers regularly for Legionella, yet it remains one of the hardest hit in the number and severity of its outbreaks because of its population density, worn infrastructure and the high levels of sediment in its water, David Pierre, director of water safety programs at water-treatment company LiquiTech, said in a Gothamist report.

Sediment “ can be a food source” for the bacteria, he told the publication.

A handful of other states have either a testing or water management requirement, typically limited to hospitals or schools. The Joint Commission, which issues accreditations for heathcare facilities, addresses Legionella in its water management program requirements.

New York City has been requiring building operators to test their water cooling towers since 2015, when it was hit with an outbreak that sickened almost 140 people and led to 16 deaths.

But it’s been inconsistent in enforcing its testing requirement, a Gothamist review found. About 1,900 of the 4,928 registered cooling towers in New York City have not been inspected by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene since 2023, and 85 have no record of inspection by the city, the Gothamist report said.

“There is, of course, always more that we can do to advance our prevention efforts,” the city’s acting health commissioner, Michelle Morse, said in a WNYC news report last month.

Testing limitations

Lab culture testing is considered the gold standard for legionella testing, according to the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration. “With proper sampling, positive Legionella culture results reliably indicate that the bacteria were present at the sampling site (i.e., culture methods have a very low false-positive rate),” the agency says.

The roughly two-week delay in getting lab culture results back isn’t the only drawback to the tests, said Rankin. If the test is used after heat or other treatment has been applied to rid a system of bacteria, it can miss one of the most lethal forms of Legionella, he said.

“Research shows that if you expose Legionella to a heat shock – 180 degrees Fahrenheit, 70 degrees Centigrade, for one hour – the most dangerous form of Legionella is not killed by it,” he said. “It goes into this dormant state. That dormant state will never be detected by a lab culture test.”

To address that shortcoming, some building operators are using a lab culture test every three months and, in between those testing dates, applying an antibody test, Rankin said.

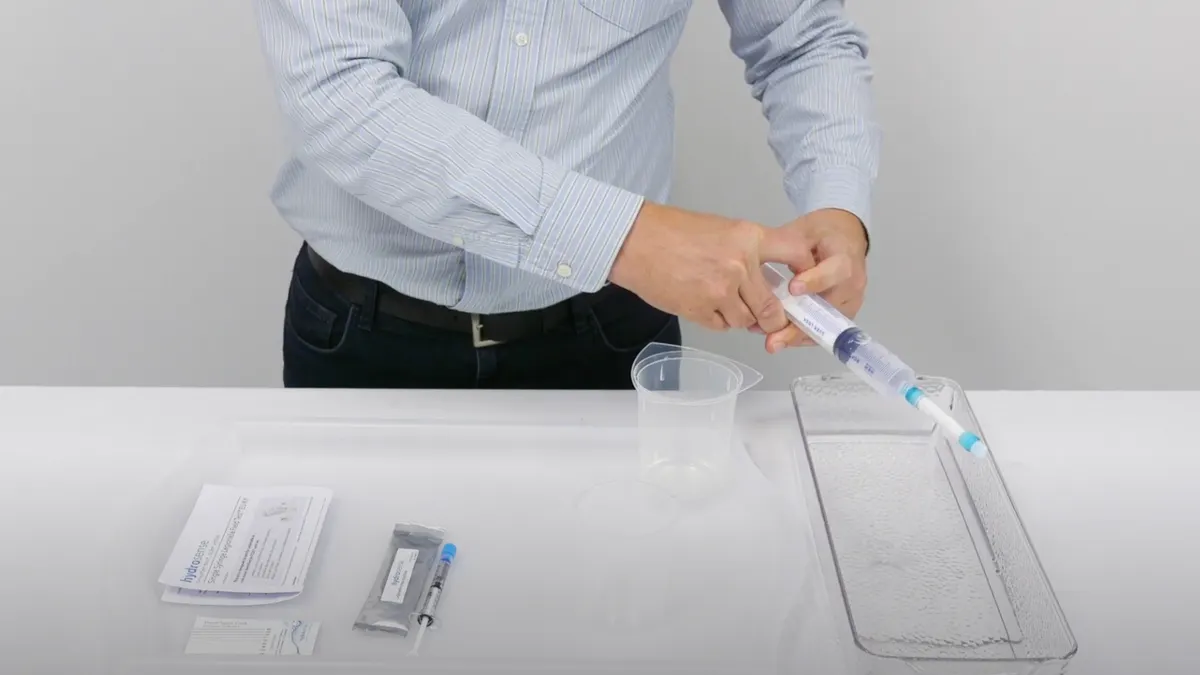

Antibody tests can capture bacteria that the lab culture misses after a heat or other treatment is applied. It produces results in about half an hour, making it almost a real-time snapshot of what’s happening in a water system, according to Rankin, whose company manufactures one type of antibody test, called a lateral flow immunochromatographic assay test. Direct fluorescent antibody assay is another type of antibody test.

“That means, if there’s a problem, the test detects it while [the building team] is standing right there, and they can do something about it,” said Rankin. “That means you’ve got that risk down from a two-week period, where everyone could be exposed, to [immediately] shutting down a cooling tower or, if there’s just a bit of Legionella, you can deal with it using a biocide and clean the system.”

Polymerase chain reaction, or quantitative PCR (qPCR) testing, is another type of test that can be used in the interim between lab culture tests, according to IWC Innovations, a qPCR testing company. This type of test also produces results more quickly than lab culture tests, the company says on its website.

It “provides rapid results, typically within 24-48 hours, allowing for swift action if necessary,” the company says.

For facility managers that want to stay ahead of an outbreak, it’s less important whether they use an antibody test or a qPCR test than that they use a mix of tests rather than relying on only one, Rankin said.

“Most of the folks we deal with in the water management space tend to use at least two different tests [whether it’s] a test such as qPCR or our test [in conjunction with a lab culture test] so they don’t have any blind sides,” he said.