Dive Brief:

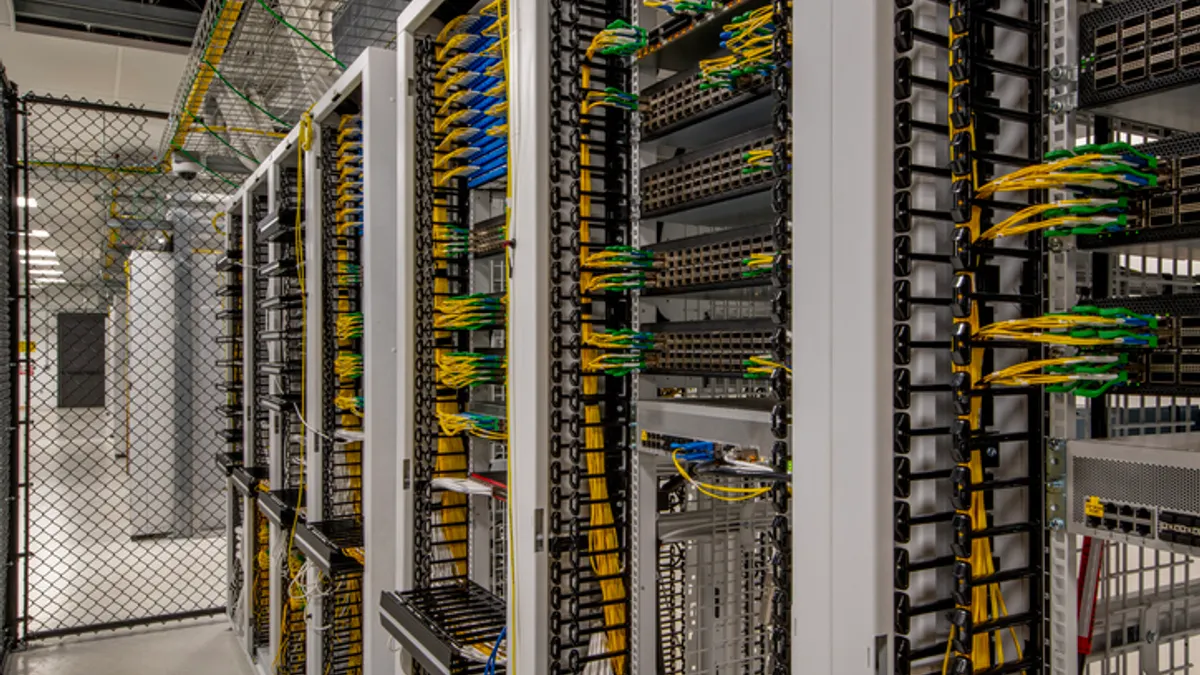

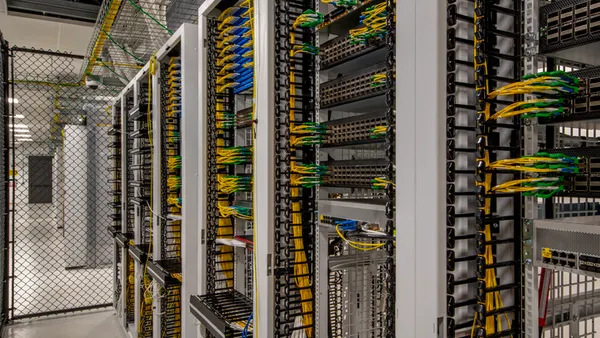

- Two computing facilities operated by Prime Data Centers have earned the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star certification, placing them in the top 25% of U.S. buildings for energy efficiency, the Texas-based technology infrastructure company said last week.

- Located in Dallas and Sacramento, the facilities “emphasize efficiency-driven design, advanced monitoring and benchmarking, and operational best practices intended to reduce energy consumption without compromising uptime or performance,” Prime said in a news release.

- Hiigh-performance computing facilities face growing scrutiny from elected officials, planning councils, environmental groups and consumer advocates over their impact on water resources, energy costs and the natural environment. Responding to local pushback, developers abandoned 25 major U.S. data center projects in 2025, quadruple 2024’s figure, according to a Heatmap Pro analysis released this month.

Dive Insight:

Prime Data Centers has ambitious energy and water-use goals in the near term, according to its 2025 sustainability report. Among other goals, it plans to pursue Energy Star certification for all of its U.S. data centers that would be eligible for a program EPA calls Designed to Earn the Energy Star status. The program targets data centers that are in the design or construction phase and achieve an Energy Star design score of 80 or higher.

“Energy Star recognition demonstrates that our facilities are performing at the highest standards as we continue to expand our footprint,” Sara Martinez, vice president of sustainability at Prime Data Centers, said in a statement.

Prime’s 20-megawatt Dallas facility and 26-MW Sacramento facility both use a combination of closed-loop air and liquid cooling, reducing energy and water usage relative to evaporation-cooled facilities. Both are committed to using 100% renewable energy to power their operations, the company says.

Prime is not alone in seeking to mitigate or offset its facilities’ environmental impact. Other data center operators and tenants have long sought to do the same.

Microsoft, for example, has contracted for more than 34 gigawatts of carbon-free electricity generation — more than the total summer generating capacity of Washington state, its home base. Its supplier code of conduct requires its vendors, “where possible,” to transition by 2030 to 100% carbon-free electricity for goods and services delivered to Microsoft.

But as they rush to scale computing capacity and electricity supplies to power their AI ambitions, big technology companies’ near- to medium-term sustainability goals appear out of reach. After several years of decline, Microsoft’s total greenhouse gas emissions jumped more than 23% last year, according to its most recent sustainability report. Google’s greenhouse gas emissions have risen more than 50% since 2019.

Meanwhile, technology companies without strict environmental goals have drawn ire from data center neighbors and environmental activists. A lawsuit filed last year in Tennessee alleges Elon Musk’s xAI flouted environmental regulations and exacerbated local air pollution when it deployed more than 400 MW of gas turbines to power its Colossus data center in Memphis.

Utility ratepayer advocates and some energy system analysts also say that data centers increase retail electricity costs, particularly in regions where they’re heavily concentrated, like northern Virginia. Those concerns are helping to fuel the public pushback causing data center delays and cancellations.

Earlier this month, Microsoft said it would “pay its way” for the grid upgrades and other energy investments needed to support new data centers, becoming the first major tech company to do so. OpenAI said it would do the same for its large-scale Stargate data centers.

For its part, Prime Data Centers says it continues to look for ways to reduce its data centers’ impact. The company diverted an average of 83% of the waste generated at its active U.S. construction sites in 2024 and is piloting “zero waste to landfill” construction methods at new sites, according to its sustainability report. By 2030, it aims to use hydrotreated vegetable oil — a diesel alternative with low net greenhouse gas emissions — as the main fuel in its data centers’ backup generators.