Dive Brief:

- Researchers saw a modest drop in the rate of respiratory infections in people who live in long-term care facilities after upper-room germicidal ultraviolet lights were added to common areas, but the findings don’t necessarily support widespread use of the technology.

- “Air cleaning technologies remain an enticing option to prevent … respiratory viral infections since they offer the promise of reducing risk,” Michael Klompas, a Harvard medical researcher, said in a commentary on recent research on UV effectiveness. “The available data thus far, however, show a limited impact on preventing infections.”

- Researchers in Australia published findings last month that showed UV lights cut the rate of infections in long-term care residents by a modest but statistically meaningful amount, suggesting the technology could play a role in settings where people are prone to infections. “If shown to be cost-effective, [UV lights could be useful] in preventing seasonal respiratory infections and protecting vulnerable populations,” the researchers said.

Dive Insight:

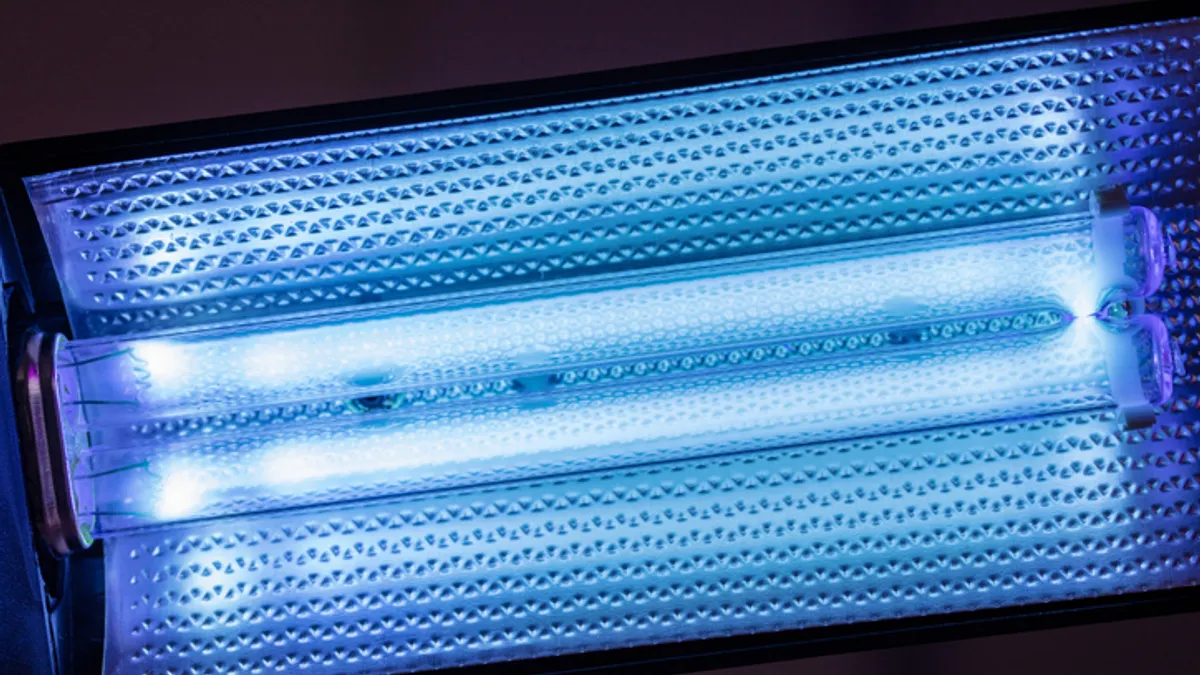

Particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have been looking at the use of ultraviolet light, which can kill airborne pathogens, as one way to reduce the spread of infectious diseases.

The Australian research stands out because it tests UV lighting in a real-world setting, said Klompus, who reviewed but did not work on the study. “To my knowledge, [this is] the first randomized clinical trial to report on the real-world impact of air cleaning technologies in nursing homes,” he said.

In the researchers’ study of four long-term care facilities, residents came down with just under 600 cases of respiratory infections, split almost down the middle between those who contracted the infection during the test phase and those who contracted it during the control phase.

The UV lights “did not result in a significant difference in the incidence rate per zone per cycle,” the researchers found. But in a follow-up analysis that looked at the cumulative rate of infections over the study period, rather than by cycle, the researchers found the UV lights reduced infections by 12.2%.

The follow-up findings make the lights “a potential adjunct to existing infection control practices for vulnerable residential populations,” the study said.

But in other clinical settings, as long as the facility meets ventilation standards, the lights might not be warranted, Klompus said.

“Clearer data are needed to justify the expense and complexity of adding air cleaning technologies to clinical spaces that already meet contemporary ventilation standards for health care,” he said.

Because of limitations in the way the study collected its data, it’s not clear how much more, or less, effective the lights would be if some variables were different, he said.

Among other things, there was no rigorous analysis of the respiratory infections that were reported, so every cough or sore throat that residents reported was included in the mix. “Given that the spectrum of illness caused by respiratory viruses is wide, the symptom complex used by the investigators was neither sensitive nor specific,” he said.

The facilities also had other control measures in place, like requirements for staff to wear masks and limits on how close residents could stand next to one another, so the research can’t distinguish how much different the outcomes would be absent those other measures.

Nor was there any accounting for how well the ventilation systems were working.

These limitations, he said, “create uncertainty about the potential impact of germicidal UV.”