How easily— and at what cost — facility managers and building contractors can access HVAC, fire and other codes is at the center of a battle that’s splitting the nonprofits that develop the codes as they try to fight tech companies that are building compliance tools around their work.

“We’ve had a system for developing codes in this country that’s worked for close to 125 years,” Gabe Maser, senior vice president of government relations and national strategy for the International Code Council, said in an interview. “We want to preserve this private sector-led system that’s been such a success.”

At issue is whether the developing bodies retain copyright protection of their work if their codes have been incorporated into law by reference. “Incorporated by reference” means a code is mentioned in the law but not reproduced as part of it. Virginia, for example, incorporates the 2021 edition of the International Fire Code into its Statewide Fire Prevention Code, but the text of the code isn’t reproduced in the state standard.

“The codes and standards referenced in the IFC shall be those listed … and considered part of the requirements of the SFPC to the prescribed extent of each such reference,” the Virginia code says.

After years of getting mixed results in courts over whether they retain copyright protection of their work if their codes have been incorporated into law by reference, the ICC and other standards development organizations, or SDOs, are supporting a bill introduced in Congress in June.

The Pro Codes Act, H.R. 4072, sponsored by Reps. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., Deborah Ross, D-N.C., Lance Gooden, R-Texas, and Dina Titus, D-Nev., would make it clear that SDOs retain copyright protection for their work, even if the codes have been incorporated into law by reference, as long as they make read-only copies of the codes available to the public for free.

It’s a “‘win-win-win-win’ solution,” ICC and other SDOs say on a website they host in support of the bill. “The public gets free access to important codes and standards [and] SDOs maintain copyright protection for the codes and standards they develop.”

SDOs make money by licensing their codes and updates, selling value-added publications and tools and providing compliance training, among other things.

How much of an impact on their revenue the act would have if it were to become law differs based on the SDO’s mix of revenue sources.

“Yes, they’re going to put [the code] online, in a preview format, to maintain public access, but the SDOs can still ensure their training is copyrighted,” said Maser. “If you [as a user] want additional functionality, you’ll be able to download it or add notes or share it with colleagues — things like that. That’s something you need to pay for.”

Third-party compliance tools

If enacted into law, the bill could make it harder for tech companies that offer digital compliance tools to make money off the codes, because they need more than read-only access.

“For-profit companies — which contribute nothing to the code development process — [are selling] unpermitted and erroneous copies of these codes,” the SDOs say on their website.

The tech companies say the courts, despite the mix of rulings, have been clear on one central point: once the codes have been incorporated into law by reference, they become part of the law and must be made publicly available.

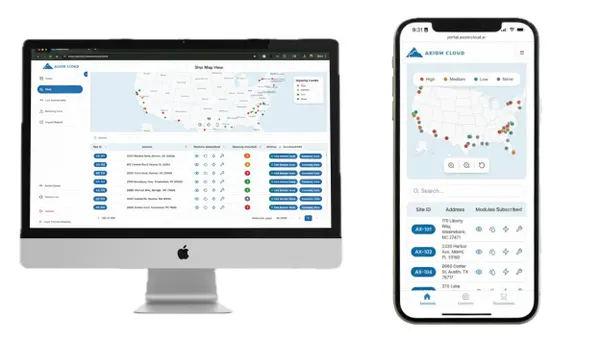

“Courts always land on the same side,” Scott Reynolds, co-founder and CEO of UpCodes, said in an interview. “When something is enacted, and citizens and builders and contractors are mandated by the government to follow it, it’s the law. It has to be in the public domain. People need to be able to see it.” UpCodes’ software incorporates codes into compliance tools it sells.

ICC and the American Society of Civil Engineers sued UpCodes in 2017 for reproducing its codes, including codes incorporated into law by reference, in its compliance tools. Both sides sought summary judgment, but in 2020 the court said the case must go to trial to resolve contested points having to do with the intermingling of codes that have and haven’t been incorporated into law. But on the core question of public availability, it said, there’s no ambiguity: If a code is incorporated into the law, it’s in the public domain.

“No one can own the law,” said Judge Victor Marrero of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, quoting from a 2019 Supreme Court decision over a related matter. “Every citizen is presumed to know the law, and it needs no argument to show . . . that all should have free access to its contents.”

For facilities managers and others who use the codes, losing access to them in tools offered by companies like UpCodes could raise their cost and make compliance more difficult.

“It’ll be a very large financial burden to afford those code books,” Ray Shipman, a building official for DuPont, Washington, said in an interview. “It was like that in the past. I would continually have to buy them to get access to certain portions of the code. I would bet each code book is almost $200 now, so you’re talking, like, $5,000 to access all the codes you need.”

Shipman said the third-party tool he uses has made compliance easier because it makes the codes searchable and provides AI assistance. “I have everything at the tips of my fingers on the job site on an iPad,” he said.

Split community

This is the second go-round for the Pro Codes Act. Issa and Hall introduced the bill in the previous Congress, where it passed the House Judiciary Committee by a 19-4 vote and just missed a two-thirds majority procedural vote to bring it up for consideration on the House floor.

“The Pro Codes Act strikes a critical balance between enabling public access to codes and ensuring copyrights are protected and organizations are properly compensated and incentivized to create and update the standards we need to keep the American people safe and healthy,” Rep. Ross said in a statement when she and Rep. Issa reintroduced the bill in June.

But not all SDOs are on board. The trade-off to get copyright protection by making a free preview version available isn’t a viable solution for all of them, Tom Costabile, executive director and CEO of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, said in an email.

“It would impose sweeping mandates that destabilize copyright protections and penalize the very organizations that develop the voluntary standards our industries and infrastructure rely on,” he said.

The bill is backed by ICC, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, the National Fire Protection Association, the Fire and Emergency Manufacturers and Services Association, the Green Building Initiative, the National Electrical Manufacturers Association and others. It’s opposed by a coalition that includes ASME, ASTM International, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and SAE International.

“This bill would [impose] a sweeping, one-size-fits-all ‘fix’ that benefits only [a very small subset of standards organizations] while undermining the broader standards system,” these SDOs say on their website opposing the bill.

“The fundamental premise of the Pro Codes Act — eroding copyright — is a blunt instrument that treats all SDOs the same, and they most decidedly are not,” Costabile said.

Maser said the split isn’t stopping the SDOs from finding a compromise. “There are a few SDOs that have been super constructive in this process,” he said. “Maybe they haven’t come out as supporters yet. They have a couple of things around the edges that they’d love to tweak if they can.”

The bill has been referred to the House Judiciary Committee, but no action has been scheduled.