The number of states and localities with panic button laws is small but growing as incidents like the Manhattan office building shooting in July raise concerns over worksite violence.

“It takes an incident to put [the need for panic buttons] in your mind,” says Kenny Kelley, founder and CEO of Silent Beacon, a company that competes in the panic button space.

Last year, New York lawmakers enacted the Retail Workers Act that requires employers to create a violence prevention plan and, if they have at least 500 workers, give each employee a panic button.

A Washington state law that took effect earlier this year requires hospitality businesses to give panic buttons to custodians, security guards and housekeepers. Illinois has had a law on the books since 2019 requiring hotels to give their workers panic buttons if they go into guest rooms alone.

About half a dozen states, including California and Virginia, either require or recommend panic buttons for employees, typically in the healthcare, hospitality or retail sectors. Many of these states plus several others also have so-called Alyssa laws, which require schools to install panic buttons in classrooms or provide them to teachers and staff. The laws are named for one of the students killed in the 2018 Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Florida.

Municipalities are passing laws, too, with almost a dozen California cities requiring hospitality employers to give their workers panic buttons.

Kelley launched Silent Beacon in 2013 as a consumer product for joggers and others who need to summon help if they have an accident or emergency but the company shifted gears to facilities after COVID-19.

“Businesses started contacting us,” Kelley said in an interview. “You have 2.6 million home healthcare nurses going out in the community. Forty percent have been assaulted. Real people were still going out despite COVID. So we made that pivot with an online dashboard for businesses.”

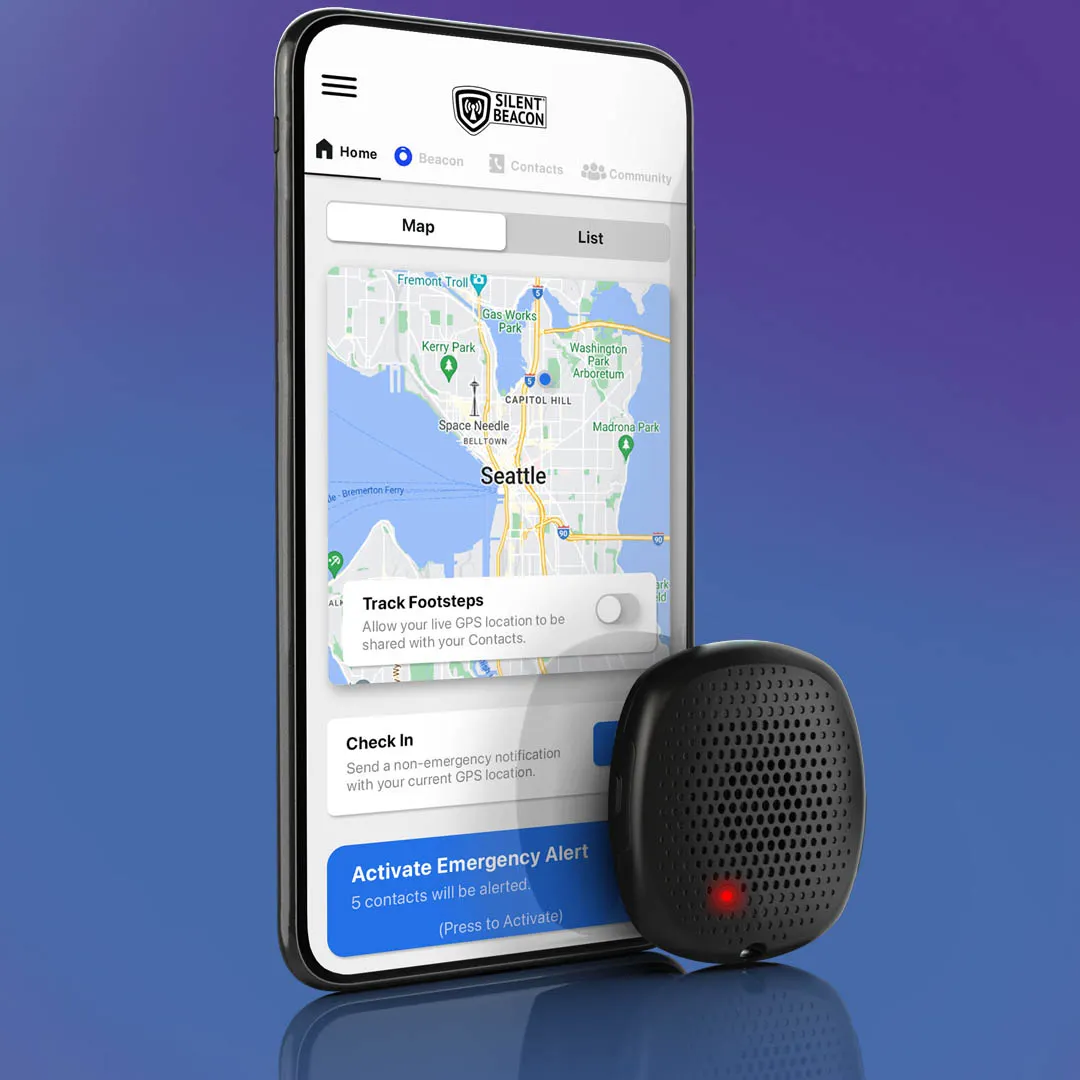

Kelley’s company makes its devices available on a licensing basis. Organizations lease the devices and use a dashboard to configure how they want the alerts to work.

“It can go to whoever the company decides,” Kelley said. “It could be 911. It could go to internal security. It could go to the manager. It could go to 911 and the manager.”

Alerts can go to personal contacts as well. “Loved ones, friends, coworkers — they would get a text message, email or push notification saying you’re in an emergency: ‘Here’s the location; you better check it out.’ You have redundancy touchpoints.”

The devices can be kept on silent mode. “You can place a call but it doesn’t look like you pressed a button,” Kelley said. “You can also mute it, so it doesn’t look like anything is happening. You can press the button again, unmute it, and it’s back.”

An employee in Chicago used the device recently to summon an emergency response team when a co-worker appeared to be in a personal crisis.

“They were dealing with a mental illness,” Kelley said. “The person was running towards the highway. The [co-worker] was able to just press the button [to summon help] while talking to the person as they’re running. … With radios and cellular devices, all these products, you have to engage with the devices — focus on them — to receive help. Here, you’re able to just worry about the situation.”

Kelley touted the company’s approach to privacy. “When you’re using a cellular product, the [cellular company] is constantly pinging your location,” he said. “Because we piggyback off your smart phone, we don’t broadcast anything until you’re in an emergency. We’re able to keep you under a veil. No one knows your location. … For the online dashboard, all we ask for is the name, phone number and email address [of your workers]. There’s no personal information. If they’re in an emergency, they press the button. If they’re not in an emergency, we don’t know your location.”

Motorola Solutions, Relay and Verkada are some other companies competing in the space.

“In the early years … I would go to these meetings to look for investors,” said Kelley. “This was in 2013, 14, 15. They’d laugh at me. ‘I’d just use my cell phone if I were being assaulted.’ Fast forward now. You don’t have to educate someone how [that doesn’t work] if someone has a gun. It was an uphill battle.”

As workplace incidents mount, it’s no longer an uphill battle, Kelley said.